How Aerosmith and Run-DMC Begrudgingly Made a Masterpiece

Initially, neither group was excited about collaborating for “Walk This Way.” The rest is history.

It was, like many great breakthroughs, both a brilliant idea and the worst idea you’ve ever heard: Get Run-DMC and Aerosmith in the studio together, force them to perform a hybrid, rap-boosted, ebony-and-ivory version of an Aerosmith hit from the ’70s, and then make a video about walls coming down, etc. Genius, right? Let’s go! Aerosmith, corroded rock behemoths in a slump, were sort of dazedly into it; Run-DMC, coming into their power as hip-hop’s first superstars, were sullen and wary. But it happened—in retrospect it had to happen—and with 1986’s goofy, clankingly enjoyable “Walk This Way,” rap music was big-banged into being as mainstream entertainment.

So at least argues the Washington Post staffer Geoff Edgers in his new book, Walk This Way: Run-DMC, Aerosmith, and the Song That Changed American Music Forever. “Before ‘Walk’ struck in 1986,” writes Edgers, “hip-hop was a small underground community of independent labels and scrappy promoters. After ‘Walk,’ it became a nation, a genre that would soak itself into virtually every element of culture, from music and film to fashion and politics.”

A grand claim, Geoff Edgers. A mighty pitch. And the question with a book like this—a book that zeroes in on a particular happening or art moment and then extrapolates boomingly outward—is always: Is there enough there? Enough action at the core, that is, and enough concentrically moving energy to prevent the narrative from collapsing in on itself as it stretches to book length? The answer in this case, I am happy to report, is yes.

However you feel about “Walk This Way” the song—and it’s no “Like a Rolling Stone”; it’s no “Sweet Emotion”; it’s no “Sucker MC’s”—as a nexus of forces, it gives and keeps on giving. The conditions of its production were, haphazardly and downtown New York–ishly, kind of an aesthetic crucible. And its blockbuster crossover appeal—the first almost-hip-hop to tickle the ear of the mainstream rock fan—demonstrably reformatted pop culture. (Also: alerted the world to the skills of the producer-impresario Rick Rubin.)

As Edgers traces the arcs of Run-DMC and Aerosmith toward their wacky intersection in Manhattan’s Magic Ventures studio, he is basically writing a book in two genres: a conventional rock biography (the kind of book in which the lead singer passes out onstage while the band is playing “Reefer Head Woman”), and a cultural history of early hip-hop. That he keeps the tone more or less even as he toggles back and forth is to his considerable credit.

Aerosmith in the mid-’80s was in the dopey doldrums; communication had broken down between lead singer Steven Tyler and guitarist Joe Perry, the music was crap, and the air was thick with substances. How to get this toxified cash cow back on her feet again? How about a novelty single with some of those rap kids? It was Rubin’s idea: He was producing Run-DMC’s third album, Raising Hell, and wanted one track that would go beyond the group’s current audience and reach into the suburbs. (As a record exec put it to Edgers: “It was impossible to get them played on pop radio. Not hard. Not even in the realm of possibility.”) And Rubin was an Aerosmith fan.

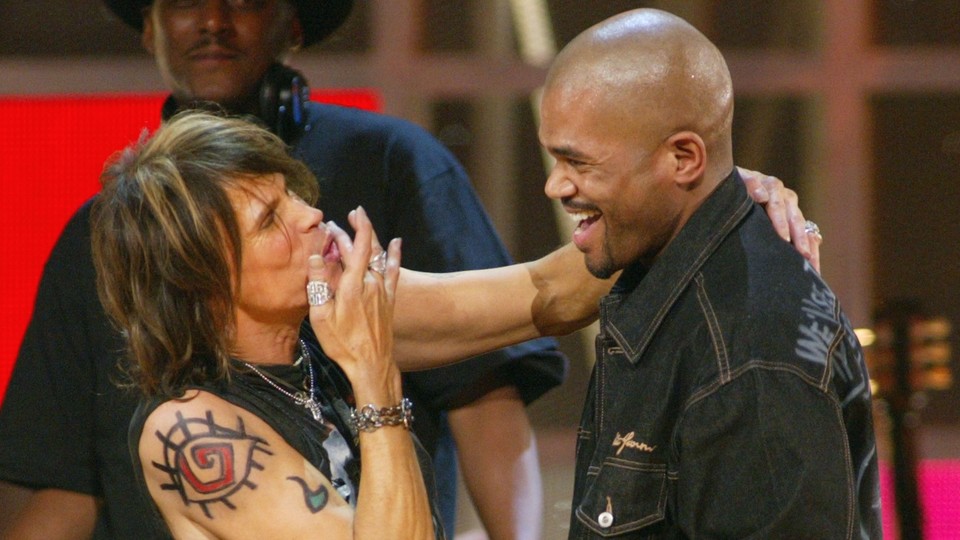

Thus did a degenerated classicism come up against the hard edges, huge-but-minimal beats, and modernist ferocity of the incoming hip-hop movement. Aerosmith was paid $8,000. Getting Run (Joey Simmons) and Darryl “DMC” McDaniels down to the studio took all the persuasive muscle of DJ/diplomat Jam Master Jay. Once there, the pair “huddled on the couch with Big Macs, grumbling something about a stolen car,” and showed no interest whatsoever in Perry or Tyler.

The words were also a huge problem. The idea was that Run-DMC would perform, in their own style, the lewd polysyllabic moonshine of Tyler’s original “Walk This Way” lyrics: You ain't seen nothin’ / ’Til you’re down on a muffin / Then you’re sure to be a-changin’ your ways. The rhythm was okay; Tyler was metrically adept, with his own species of raddled proto-flow. But learning and then obediently mouthing his words? Run in particular was unamused. “This is hillbilly gibberish ... Country bumpkin bullshit!”

The beat, on the other hand, they already knew. The four seconds of bare kick drum, snare, and high hat that introduced “Walk This Way” had long been a DJ favorite, a staple of park jams in the boroughs of New York. The members of Aerosmith bicker to this day about who actually made that beat: Tyler, who knows his way around a drum kit, maintains that he invented it in a spasm of percussive inspiration (“I sat behind the drums, and the rest is history”). But then he concedes that it was drummer Joey Kramer who added the high-hat accent, the “bark” or “choke” of a high-hat opening and snapping shut, which is pretty much the whole point—the compressed, pistonlike punch that it puts on the downbeat.

The DJs in Queens were not concerned with the beat’s authorship: They’d already clipped it from the song. “We were going for the beats,” Run tells Edgers. “We would say, ‘Pick up that joint from [the Aerosmith album] Toys in the Attic and scratch the beginning.’ If you got past that, the DJ made a huge mistake.”

So you could say it was rather a retrograde business, really; hip-hop, having artistically appropriated the beat from “Walk This Way,” was now being dragged back into it, back into the leering, writhing body of the song, by Rick Rubin. Somehow he pulled it off, though: Perry cranked his riff, Tyler flourished his scarves, Run and DMC learned their lines, and it all worked out. Aerosmith was reanimated and had a string of hits into the ’90s; Run-DMC, in their unlaced Adidas, marched gigantically into stadiums worldwide. Win-win.

As for Rick Rubin, his career highlights would include Johnny Cash’s American Recordings and Jay-Z’s “99 Problems.” In 1986, though, he made his single greatest contribution to the universe of sound, and it wasn’t the three angelic blurts of needle-noise, the scratch-stutters that announce the riff in “Walk This Way.” It was the clean, knelling tone of Dave Lombardo’s ride cymbal on Slayer’s Reign in Blood. Did that also change music forever? Too soon to tell.